This story originally appeared in HuffPost’s Books newsletter. Sign up here for weekly book news, author interviews and more.

When I think of some of the early forces that shaped my concept of work, and more specifically women in the workplace, it was actually MTV’s hit reality show “The Hills.” The “unscripted” series, which aired in 2006, focused on Lauren Conrad and her newfound Los Angeles life as an intern at Teen Vogue, a job that appeared to me as an impressionable young viewer to be the epitome of working-girl success and the ultimate culmination of career ambition.

Week after week, I tuned in to watch Conrad continually struggle to find the balance between her personal life and the growing demands of her professional one. It didn’t take long for me to form the lasting belief that gaining and keeping a successful career as a woman (at Teen Vogue no less) meant missing out on birthdays, time with loved ones and weekends spent working. Thus, the “girlboss” became embedded in our collective consciousness, well before the term had ever been coined.

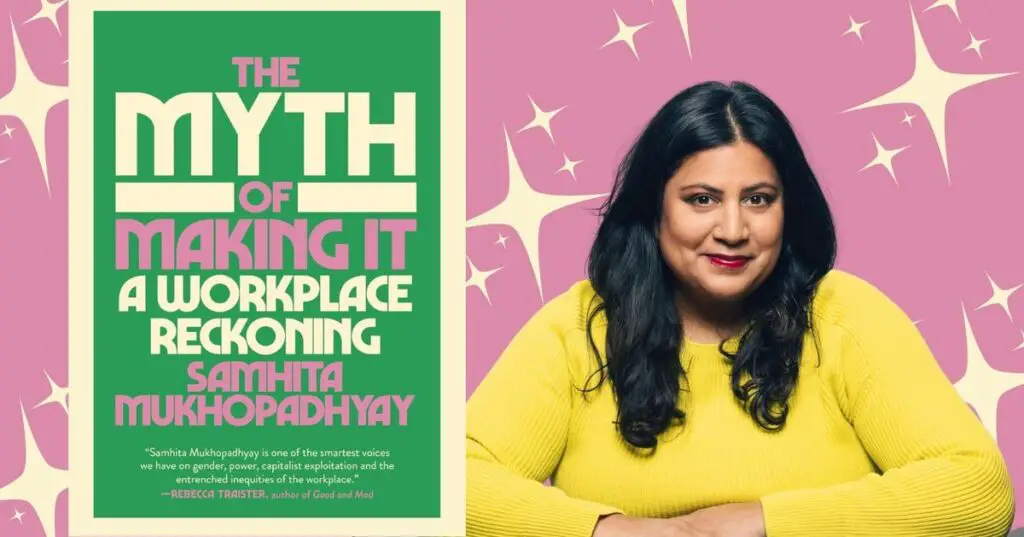

Despite “The Hills” being an entertainment show of questionable validity, much of what it seemed to reveal about what it takes to be “on top” is surprisingly accurate and something that author and former executive editor of Teen Vogue, Samhita Mukhopadhyay, is very familiar with. In her newly released book, “The Myth of Making It,” Mukhopadhyay details her glitzy beginnings at the fashion magazine and how it felt to finally be in the folds of New York’s editorial elite. It was all enough to sustain the fallacies we use to help us overlook the causes and consequences of late-stage capitalism and an American culture that thrives on “the hustle” — until the day that it wasn’t.

A factually supported conversation about toxic productivity, labor exploitation and neoliberal trickle-down feminism, Mukhopadhyay’s memoir-of-sorts calls for a “workplace reckoning” if any of us are to survive in a time when, statistically, we’re working more than ever before and wealth gaps are widening.

Mukhopadhyay is now the editorial director at The Meteor, a collectively founded and feminist media company focused on platforming the “work of BIPOC creators, LGBTQ+ folks, and all groups traditionally underrepresented in media.” She recently took the time to speak with HuffPost about “The Myth of Making It,” the death of the “girlboss,” and her vision for a system that truly embodies work-life balance.

I mentioned the way Teen Vogue was portrayed on shows like “The Hills” or “The Devil Wears Prada” and how that work mentality may have had a formative influence on younger viewers. I’m curious if this echoes your own personal experience working in that environment?

By the time I got to Teen Vogue, I was a bit older and was already pretty set in who I was so I hadn’t internalized that specific culture quite yet. But, what I had internalized prior to that was that I had gotten there based on hard work, discipline and by working my networks and making all the right connections. So, I felt that if I was going to prove that I belonged there, then I just was going to work my ass off, even if I was coming in as an already senior person. I think that was the one thing that [eventually] really started to disentangle for me, was this idea that I was lucky to be there [versus] the other way around.

Speaking about that kind of toxic productivity that’s so pervasive in work culture, why do you think there has been such an increase in conversations surrounding it?

I think people have started talking to each other about workplace conditions. One of the drawbacks of what I call in the book neoliberal feminism or lean-in feminism is the idea that you personally can overcome every obstacle that comes your way. You can overcome the pay gap, you can overcome how working mothers are treated or are overlooked for promotion when someone decides to have a child. When we internalize these beliefs, it keeps us alienated and isolated from each other. It kind of inherently sets up this competitiveness. Whereas now, I think that women are having conversations with each other in earnest, both about how hustle culture has not been successful in their own lives and how these kinds of myths that we’ve internalized about what it means to be successful haven’t actually brought us success or happiness.

Aside from the fact that women are relatively new to the workforce and holding larger positions of power compared to their male counterparts, why do you think women and people of color are disproportionately affected by this internalization of hustle culture?

What I really tried to spend the beginning of the book laying out is what came before. Neo liberalization of workplace feminism has deep roots in the labor movement, and somehow it turned into this debate about our personal choices. Through the ’70s and ’80s, the whole “working girl” narrative perpetuated this idea that women have all these choices, which is great and, like, we want that, but it also made women be culpable for those decisions without recognizing that we live in a society that does not support working mothers, and just in general, we have an entire infrastructure that exists just to make women feel bad about their decisions.

So would you then make the argument that “girlboss” as a concept was co-opted to be something inherently anti-feminist?

What I really talk about in the book, and specifically in the chapter about the death of the girlboss, is that it’s less about [criticizing] some of that entrepreneurial and girlboss-y advice, and really about articulating what happens when you pair that type of neoliberal trickle-down feminism with the late-stage capitalist model of startup culture where it’s all about the bottom line, about productivity and about growth at all costs.

How would you categorize this book? Would you consider it more of a memoir or a kind of self-help book, or something completely new?

It’s something new. I’ve been describing it as a reported memoir where I do share my own experiences, but I pair it with other people that I talk to that are having these experiences — research and experts that really helped me shape [the book].

Where can we go from here in terms of restructuring the way people work?

I can speak to what I hope people get out of the book and what they do with it. I do think one of the main things that a lot of people are feeling right now is alienation so, first and foremost, I just hope that people feel a little less alone when they read this and when they see someone who, on paper, has it made, but then all of that kind of cracks in that facade. And then the second is, I talk about this concept in the book called the “margin of maneuverability,” which is the distance between what you can do in your own life versus what’s possible in a broader sense and for us to really take a moment to say that none of this can be overcome as individuals. We can’t single-handedly overturn the pay gap, we can’t hustle our way out of the fact that less than 10% of CEOs are women. There’s no amount of day planners or SoulCycle classes that can overcome that type of inequality so where are the places that we can connect with people?

I think it’s really easy right now to just say “work sucks,” which is fine for the time being but ultimately, like, that’s not going to sustain you, that’s not going to sustain you emotionally, spiritually, and that’s not better for our society. In order to actually create the spaces that we feel good about, we’re going to have to start having these conversations in earnest. That’s really what I hope people start to think about after reading the book.

Keep reading to see a list of Mukhopadhyay’s favorite authors and books on healing, activism and labor in America.

HuffPost and its publishing partners may receive a commission from some purchases made via links on this page. Every item is independently curated by the HuffPost Shopping team. Prices and availability are subject to change.

“Women, Race & Class” by Angela Y. Davis

Angela Y. Davis is an icon of the civil rights movements, a founding member of Critical Resistance, a renowned feminist scholar and a fierce advocate for prison system reform. Published in 1981, Davis’ “Women, Race & Class” is a well-regarded, informed and vital work on the intersection of racism, sexism and classism in American society. It’s a detailed exploration into the women’s liberation movement and specifically the experiences of inequality that Black women face within the social structures of America. Davis’ sage prose details how misogyny, racism and classism have shaped the nation’s social, political and cultural constraints from the antebellum era to the 1960s. Davis was writing decades ago about intersectional racism and sexism as well as the ways white-dominated and middle-class social movements have often overlooked and passed over solidarity with the working class and Black people, thus creating an “otherness” for their own gain. Davis also succinctly lays out how the use of the prison system and other “dehumanizing” methods of control are actually designed to expand the disparities between Black and white women, which in turn impact modern feminist issues like housework and reproductive freedoms, hindering the vital shared experience.

“Rest Is Resistance: A Manifesto” by Tricia Hersey

There’s something inherently radical in the choice to allow your body to rest, especially within a system that seems to only place value on our ability to be in a constant state of hyperproductivity at the expense of our very bodies and well-being. For Tricia Hersey, the rebellious choice to allow herself the time to rest not only altered her life but helped in creating a movement and her book, “Rest Is Resistance: A Manifesto.” Hersey’s preface is bold and uplifting, letting the reader know that “grind culture can’t have you.” She claims this book should be viewed as a “field guide for rest resistance” and a way to “navigate the reality of capitalism and white supremacy robbing us of our bodies, our leisure, and our DreamSpace.” Hersey, who was overburdened and overworked during graduate school, endured not only rigorous academics, but work and parenting, all while the pressures of bills, family affairs and racial violence loomed overhead. She did something then to ease the growing pressure — Hersey began to nap and meditate. Discovering how beneficial and even liberating the act of rest was, she created the Nap Ministry in Atlanta, a movement that has continued to grow as Hersey uses her platform to share the ways that capitalism and racism create a sleep gap between white and Black Americans. Hersey hopes her book will show us not only these disparities, but also how to reclaim the ability to rest, since within the capitalistic system so many of us don’t know how anymore without feeling inadequate or guilty for allowing our minds and bodies much-needed rest.

“Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America” by Barbara Ehrenreich

In the late ’90s, social critic and author Barbara Ehrenreich embarked on an undercover journey working poverty-level wage jobs for a year to disprove the pervasive American belief that anyone who works hard enough will succeed. Living in several different states across the country, Ehrenreich worked as a waitress, maid, at Walmart and in nursing homes while living in some of the cheapest accommodations she could find. Through this experience, she realized that the idea of “unskilled” labor doesn’t exist and, instead, every role she took on required intelligence, mental elasticity and physical effort. Ehrenreich experienced firsthand that one full-time job is often not nearly enough to live on, let alone support a family or nurture any kind of existence that’s conducive to good well-being. This illuminating, relevant and essential work shows how Americans routinely adapt and consistently struggle, revealing the truths and costs of American “success.”

“Where We Stand: Class Matters” by bell hooks

Regarded for scholarly work and theories on race, gender, class structures and feminism, “Where We Stand” continues bell hooks’ reflections on class, but through the lens of her own experiences, activism and academic studies. Beginning with her childhood in Kentucky growing up in a working-class family, hooks writes of some of her earliest recognitions of hierarchy and how these structures are often actively denied by those with more wealth and status, specifically for the sole purpose of preventing others from advancing. She deftly shows how the “haves” maintain their status quo through exploitation of the “have-nots” and the co-optation of other social groups. Taking a deep look into class divisions and socioeconomics in a way that her contemporaries often fail to do, hooks clearly presents an illuminating and engaging memoir that’s as much about her personal life as it is about class and racial awareness.

“Give and Take” by Adam Grant

The idea that the harder your work, the more likely you are to succeed is upended by Adam Grant and his book “Give and Take.” Grant is an organizational psychologist at The Wharton School and a bestselling author who is often viewed as a preeminent thinker on influential management styles and the social science of success. After a series of studies and longer-form research, Grant writes about how creativity, motivation, generosity and our interactions with others are the true factors that can shape our fortunes. Combining fact-finding groundwork with real-person accounts, Grant lays out his thought-provoking conclusions of how reciprocity and a “giver” mentality is what will actually give you a more fulfilling life, and that selfish and Machiavellian choices are less likely to help you achieve what you want.

“We Will Not Cancel Us: And Other Dreams of Transformative Justice” by adrienne maree brown

Most of us are familiar with the term “cancel culture,” a social tool that’s often used to address abuse and aggressions in a very public way, resulting in swift and often deserved consequences. And while the concept has been helpful in platforming the voices and needs of marginalized communities, this collection of short essays by author and activist adrienne maree brown depicts how complex it really is. In “We Will Not Cancel Us,” she asks the reader to consider what happens when condemnation has gone beyond centering accountability for the purpose of transformative justice and social change, and, in the words of the book’s publisher, “what happens when people in social justice movements direct their righteous anger inward at one another?”

“What It Takes to Heal” by Prentis Hemphill

Prentis Hemphill is the founder of The Embodiment Institute and creator of the podcast “Becoming the People” who has invested decades of time and efforts into trauma conversion and other therapeutic endeavors. Formally the healing justice director at Black Lives Matter Global Network, Hemphill’s national bestselling “What it Takes to Heal” is just as invested in healing the trauma of the individual reader as in making a collective impact. Using beautifully written and compassionate prose, Hemphill imparts the wisdom that in order to heal what is around us, we must first heal our “bodies, minds, and souls,” and that by focusing on internal healing, we develop the needed tools and skills to connect with one another, thus creating a better world around us.