By Stephen J. Nesbitt, Rustin Dodd and Eno Sarris

The email landed in Cláudio Silva’s inbox on the evening of Dec. 6, 2011. One of the first things he noticed was the three letters in the subject line: MLB.

Baseball?

Silva was an NYU professor who specialized in data science and computer graphics. He had once worked at AT&T Labs and IBM Research. Those were initials he understood. But MLB? Silva grew up in Fortaleza, Brazil, a coastal city where baseball had little relevance. When he got his doctorate at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, he never bothered to learn the rules.

The email was written by Dirk Van Dall, who was working with Major League Baseball Advanced Media (MLBAM), the league’s digital arm. It was forwarded to Silva by Yann LeCun, another NYU professor and one of the world’s foremost experts on machine learning. Silva read the first few lines. It concerned a secret project in the works. “MLBAM is working with a vendor on technology to identify and track the position and path of all 18 players on the field,” Van Dall wrote. The problem, he continued, was that the resulting firehose of data would need to be compressed, coded and organized on the fly for use by broadcasters, analysts and coaches.

Van Dall didn’t mention the project could revolutionize the sport, transforming the way teams evaluate players or how fans watch games. Nor did he use the project’s eventual name: Statcast.

Silva wasn’t sold. Sharing the email with Carlos Dietrich, another Brazilian graphics expert, Silva said, “It seems interesting. But it has no academic value.”

Still, Major League Baseball wasn’t a brand to brush off. Plus, compared to other corporate pursuits, this project seemed unusually laid back. When Silva and Dietrich agreed to consult, the league gave them no non-disclosure agreements or legalese, just a CD containing player-tracking data from a game earlier that year — Aug. 2, 2011: Kansas City Royals 8, Baltimore Orioles 2. That, Dietrich would say, was the day “Statcast actually started.”

That data set spawned years of research, testing and technological innovation. Two Brazilians who barely understood baseball created a data engine — code name “black box,” because no one else knew how it worked — upon which would be built the structural bones of Statcast, the tracking system that turbo-charged another wave of the sabermetric revolution.

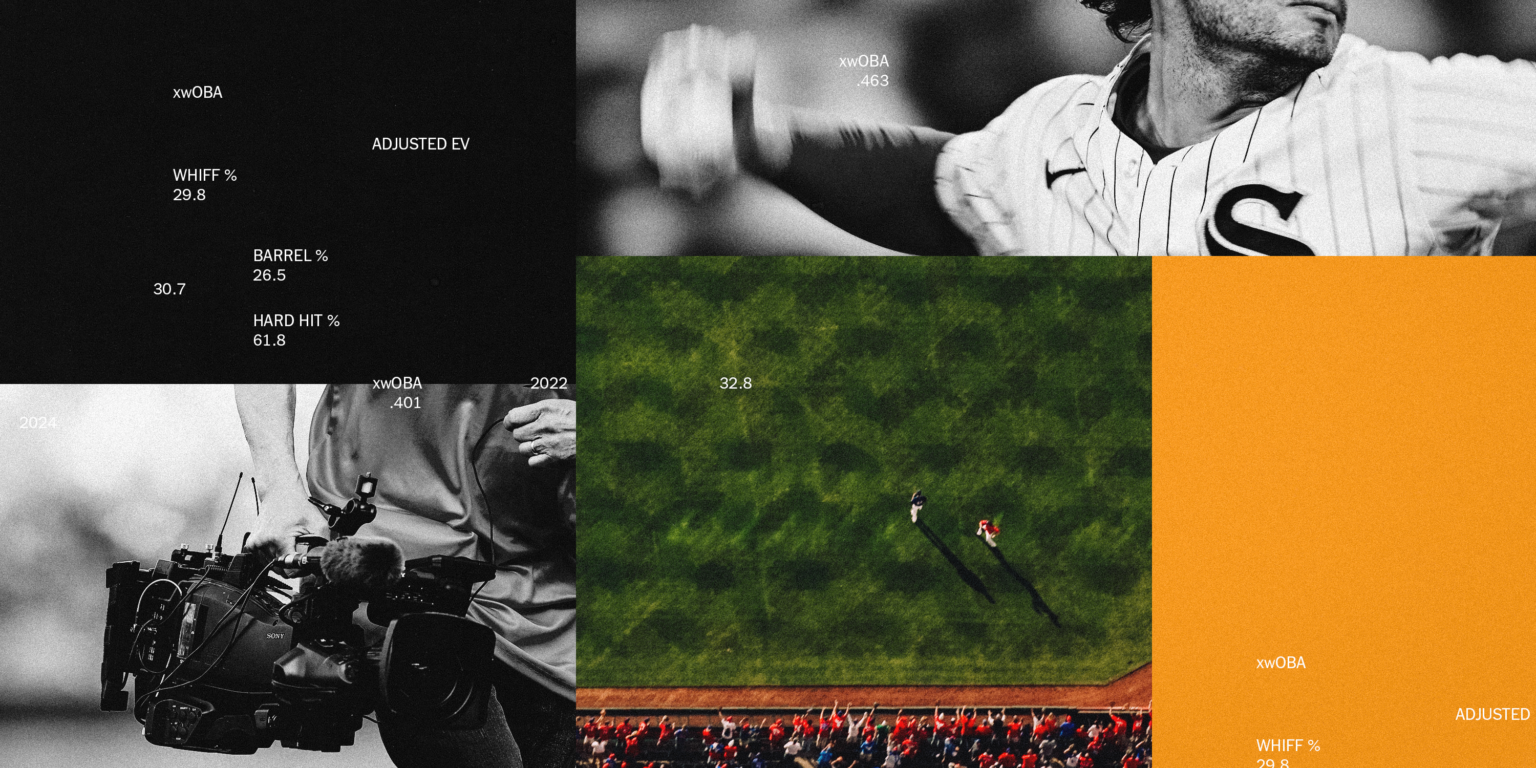

It’s been 10 years since a primitive version of Statcast debuted at the 2014 Home Run Derby. The “Statcast era” has been one of profound change. New stats have been developed and popularized as a result, and the modern baseball vernacular has swelled, with phrases like exit velocity and launch angle entering common parlance. The firehose of data has swelled analytics staffs, transformed scouting and player development, and punctured cherished beliefs. (You thought you knew how power was produced? Think again.) Statcast is everywhere — produced and promoted by the league — but not for everyone. It enthralls analytically inclined fans and irks others.

Billions of data points have been distilled into insights that have made baseball a smarter game. But a better one? That’s up for debate.

“Something of the old school feels lost,” Cubs pitcher Drew Smyly said.

“The old-school game is the past,” countered Mets designated hitter J.D. Martinez. “We can’t play this game like that anymore.”

Ten years before the email, on a Saturday night in Oakland, Derek Jeter ranged across the diamond to field an errant relay throw and flipped the ball to catcher Jorge Posada in time to tag Jeremy Giambi and preserve the New York Yankees’ lead in Game 3 of the American League Division Series. At MLB’s Park Avenue offices the next morning, debate raged. What if Paul O’Neill had been in right field instead of Shane Spencer? What if Spencer’s throw had hit either cut-off man? What if A’s manager Art Howe had pinch-run Eric Byrnes for Giambi? Where had Jeter come from?

And why, asked one league executive, can’t we measure all of that?

The seed for the Statcast project was planted.

Statcast’s red and blue circles have become familiar to a large subset of baseball fans.

“We wanted to get into the DNA of what allows plays to happen,” said Cory Schwartz, now MLB’s vice president of data operations. “But before you run, you have to walk. You have to start with the pitch, the origin of the action.”

That part became possible in the late 2000s when PITCHf/x — a system of cameras tracking pitch velocity and movement — was installed in each big-league ballpark, inundating clubs with data and ultimately spurring a pitching revolution. Conversation inside the former Oreo cookie factory in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood that served as MLBAM headquarters turned to the next frontier: a full-field tracking system.

“The holy grail has always been if you know where the players were,” said Joe Inzerillo, who led MLB’s multimedia efforts at the time. “Knowing where the ball is in baseball is great. But knowing where the players are and where the ball is unlocks all of this other data you can start to look at.”

Having edited video for the Chicago White Sox in the 1980s, Inzerillo understood the value of automating work that was usually being done manually by clubs, like creating spray charts to position fielders and craft pitching plans. But the technology to do so was in a nascent stage. Sportvision, which ran PITCHf/x, had an expensive camera array that yielded unreliable results. European soccer clubs were using various machine vision setups, but in baseball the ratio between the size of the playing surface, the players and the ball made it challenging to capture minute movements accurately.

“We didn’t want to do something people would historically look at and say, ‘Oh my God. What were they thinking?’” said Inzerillo, now an executive vice president and chief product and technology officer at SiriusXM. “If we couldn’t measure it accurately, if it wasn’t scientific, we didn’t want to put it out.”

The solution for Statcast came from a pairing of two European companies. The Swedish company Hego had a 4K camera setup that would provide a stereoscopic view of the field. (When it was clear the project was too large for Hego’s two-person operation, Hego merged with graphics giant Chyron.) Trackman, a Danish golf company that broke into baseball with a ball-tracking device engineered by a man who’d used radar to track missiles, agreed to assemble a large array of radar panels for each stadium.

In 2013, Salt River Stadium in Scottsdale Ariz., was the testing ground for the next generation of baseball tech: Sportvision and ChyronHego cameras alongside Trackman radar. The Statcast system would need to work day or night, in weather conditions ranging from downpour to sun glare to dense fog. Silva and Dietrich installed extra equipment to validate the vendors’ output. They found that Sportvision’s results were rife with errors because it smoothed curves and made assumptions for missing data.

ChyronHego amassed a war chest of data and presented it to MLB executives in New York. They built a baseball diamond in a spreadsheet and showed how, when they input a line of data, players appeared, in position, on the screen. “At that moment,” former Hego CEO Kevin Prince said, “baseball management rocked back on their chairs and said: F— me.”

MLB had its holy grail: radar to track the ball, cameras to track players.

As data began to trickle in during Statcast’s experimental stage, then-MLBAM CEO Bob Bowman and his staff began writing down everything that could be quantified in a single baseball play. They listed more than 100 ideas. They then whittled it to about 20 “golden” metrics that would comprise Phase One of the public Statcast rollout, everything from exit velocity to sprint speed to secondary leads to fielder range.

“So much of baseball record-keeping is (an) accounting of what happened,” Schwartz said. “So and so hit 30 home runs or had 200 strikeouts. That’s backwards looking. But skills analysis enables you to look forward and look at whose skills will potentially lead to better results. That’s what baseball scouts and talent evaluators have been trying to do since before our dads were here.”

Statcast would measure process — evaluating a player’s skills with more accuracy than the eye test.

Constructing each metric took careful consideration, plus a little bit of a sniff test. The initial leader for catcher pop time — how long it takes a catcher to receive a pitch and get it to second base — was Los Angeles Angels backup Hank Conger. “No offense to Hank Conger,” Schwartz said. “We knew that wasn’t right.” MLBAM intern Ezra Wise, now an analyst for the Minnesota Twins, was dispatched to watch Conger. Wise learned Conger short-hopped most throws, and the pop-time “stopwatch” halted as soon as the ball hit any object, grass or glove. Once the metric was adjusted to measure the throw to the center of second base, Conger slid to the bottom of the leaderboard and J.T. Realmuto popped to the top.

Statcast had no name when it was introduced by Bowman at the MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference in March 2014. The system was in alpha testing that season, active in just three stadiums — Citi Field in New York, Miller Park in Milwaukee and Target Field in Minneapolis. It was also installed in Kansas City and San Francisco ahead of the 2014 World Series. In Game 7, Giants second baseman Joe Panik made a diving stop and turned a game-defining double play. Statcast not only concluded that Panik had a slightly negative reaction time — he was moving toward the ball’s eventual path 10 feet before it met Eric Hosmer’s bat — but that Hosmer would have been safe if he hadn’t slid into first base.

By 2015, with the Trackman-ChyronHego set up in all 30 MLB ballparks, Statcast insights began infiltrating broadcasts and game coverage, where data like launch angle could be used to explain a home run explosion during that season’s second half. Yet the data wasn’t available anywhere fans could find it until MLB contacted Daren Willman, a software architect at the Harris County District Attorney’s Office in Houston. Willman had created a site called Baseball Savant that provided pitcher matchups, leaderboards and an advanced-stats search function. MLBAM hired Willman and acquired his site before the 2016 season, then added writer Mike Petriello and statistician Tom Tango, who had extensive experience developing baseball metrics.

With a site, a savant, a statistician and a sportswriter dedicated to Statcast, the league was ready to take Phase One public.

It didn’t take long to see their work impacting the game on the field. One day, MLBAM staff passed around an article in which an MLB hitter mentioned he was working on his launch angle.

“We were like, OK, now Statcast is in the canon,” Inzerillo said.

The Statcast era was born in the same manner that Hemingway described bankruptcy: gradually, then suddenly. As the system churned, front offices leveraged the data to turbo-charge their analytics departments. Hitters revamped their swings to put the ball in the air. The numbers on batted balls and defensive positioning confirmed the value of defensive shifts, which only increased their use. In the early years of Statcast, Dietrich, the NYU engineer, recalled sending teams charts and data on defensive formations. “You could see clearly the defensive formations changing through the years,” he said. “I don’t know if it was in response to the data we were providing, but probably (it was) because they never had that data before.”

The defensive shift had been around since Ted Williams in the 1940s. But for decades, it remained an undervalued tool. As teams turned to the tactic, Statcast’s cameras offered a level of new precision. In 2016, left-handed batters were shifted 30.3 percent of the time in bases-empty situations. That rate more than doubled over the next six seasons, to 61.8 percent. As singles disappeared, baseball moved to stop the tactic in 2023, mandating that two infielders had to be on each side of second base when a pitch was released.

If there was any doubt about the growing influence of Statcast, one only had to consider that exit velocity, launch angle and shifting were the parts that were public. So much remained proprietary — still invisible and underground — where teams were free to take the numbers and build their own models.

“It’s completely changed the game,” said one assistant general manager, under the condition of anonymity. “For a long time, we had very little capability of quantifying what our eyes told us to be true.”

From a technical standpoint, Statcast remains a marvel, a shorthand for the broader proliferation of bat-tracking technology and biomechanics that are changing player development. When MLB introduced bat speed metrics earlier this year, Martinez, the analytically inclined veteran hitter, looked at the numbers and questioned the accuracy of the data. Others just questioned the point.

“I would argue that swinging as hard as you can to hit the ball as hard as you can to get the miles per hour promotes more swing and miss,” Roberts said, “which doesn’t help me win a baseball game.”

Few major leaguers made better use of baseball’s newest analytical tools than J.D. Martinez. (Billie Weiss / Boston Red Sox / Getty Images)

For some players, there is only so much utility in the Statcast leaderboards. Blue Jays outfielder George Springer came up in an Astros organization that embraced technology. But he never gravitated toward the metrics. They can show bits and pieces, he said, but often they don’t show “the true measure of a player.”

Spend time in major-league clubhouses, and it’s not unusual to see players poking around Baseball Savant. Dodgers starter Tyler Glasnow looks at Statcast regularly, using the numbers as a second point of validation: There is how he felt on the mound, and then there is the underlying data. But across the room, fellow starter James Paxton offered a pithy rejoinder: “I can tell you if it sucked or if it was a good pitch just by looking at it,” he said. “I don’t need the computer for that.”

Some players are neither Statcast boosters nor cynics. They’re just baseball fans. Kevin Kiermaier, Toronto’s four-time Gold Glove outfielder, doesn’t use Statcast as a roadmap to self-improvement. He sees it as an avenue to learn cool stuff.

“You sit here and watch Shohei Ohtani and Oneil Cruz hitting the ball 119 mph,” Kiermaier said. “That’s incredible. I’m glad we are able to know that. Like, ‘How hard do you think he hit that?!’ ‘I don’t know!’ Now we know.”

What once felt radical is now commonplace. When Statcast debuted in 2015, Padres All-Star outfielder Jackson Merrill was 11 years old. Once upon a time, ESPN could air an alternate Statcast broadcast and it could feel like programming from the future. Now, ESPN’s David Cone can fluently discuss barrels and predictive metrics on Sunday Night Baseball, the network’s flagship broadcast.

“The stuff that we did in 2016 that was so new is just mainstream now,” said Petriello, a commentator on the Statcast broadcasts. “You can turn on any broadcast and hear people talking about Barrels and win probability, and that’s wild.”

In 2020, Statcast’s Trackman-ChyonHego setup was replaced by an optical tracking system from Hawk-Eye Innovations, a company best known for automating line calls in tennis replay. Hawk-Eye initially installed in each stadium 12 cameras running at 50 or 100 frames per second, then, in 2023, replaced five of those with 300 frames per second cameras, which allowed for the bat and biomechanics tracking.

The bat-tracking metrics — including each hitter’s swing speed and length — were once among the 100 ideas MLBAM listed more than a decade ago. As technology improves, more measurements have become possible. Limb tracking is likely next.

“There’s kind of a natural evolution,” said Ben Jedlovec, who worked in data quality for MLB for six years, “from what happened — the guy hit a home run — to how it happened — a fastball on the outside corner, a (certain) swing speed — to how the player made that happen. How did their body have them throw 99 mph? How did the hitter’s body mechanics help him time that pitch?”

Along with the three-dimensional visualizations Statcast already has, and the advent of virtual reality, there are also visualizations made possible by the advent of limb tracking. A full-field tracking system can inform comprehensive models that help us tackle questions that at first do not seem possible.

“Let’s go back to Jeter,” Schwartz said.

Today we’d be able to measure exactly how much ground he covered. We’d know exactly how strong Spencer’s arm was compared to O’Neill’s. We’d calculate the probability of Byrnes scoring from first based on his foot speed, Spencer’s arm strength and accuracy, and each fielder’s positioning. We could produce an entire other reality and see what would’ve happened to that play if any of the circumstances were just a little different.

“You can start to tinker around with things,” Schwartz said, “and see what kind of outcomes you might have gotten.”

Instead of virtual reality, these alternate realities could help the analytically-inclined fan better appreciate what they did see in that game, and the probability of an extraordinary outcome on the field. Players might be able to use limb tracking to improve their mechanics to achieve better outcomes. We’re all likely to hear and read more about how these athletes move through space in the coming years. How that knowledge filters down to us can be customized to our preferences.

If alternate reality simulations sound … out there, it’s worth connecting them to where this started. A decade later, the creation of Statcast stands as a triumph for the league and a fulcrum for the sport. But for those who worked on Statcast, it remains a brilliant accident, a random confluence of fledgling companies, novel tech and part-time engineers.

“Picture a situation where you are my manager,” Dietrich said. “I walk into your office and say, ‘Man, I have this idea. I’ll create a tracking system with this huge set of 3D cameras and a radar to capture the ball. The company that will make the 3D cameras doesn’t exist yet. The other company that will implement the radar works with golf. We’ll call these two guys that never worked with anything related to sports, and they’ll implement this metrics engine, and after a few years, we’ll have this multi-million dollar tracking system that will give us results we never saw.

“I think I would be real lucky if I had the job by the end of the day. Because it makes no sense at all.”

(Top Illustration: Dan Goldfarb / The Athletic; Top photos: Patrick Smith / Getty Images; Darren Carroll / Getty Images; Jamie Sabau / Getty Images)