Connor McDavid waited for his family in the elevator so they could sneak in quickly without being noticed. His brother hugged him first. But there were no words as the McDavids ascended the Conrad hotel in Fort Lauderdale.

It was well after midnight — hours after the final seconds of the final game fell away — and there was still little to say.

No way to make sense of almost completing one of the greatest comebacks in the history of the Stanley Cup Final. No joy in being named the playoff MVP while leading the losing team. No consolation in getting closer to a championship than he’d ever been. A single game away. All meaningless details of defeat.

When it was all over — after each Florida Panther lifted the Stanley Cup and the Conn Smythe Trophy sat untouched, after the tearful Oilers comforted each other in the locker room, and after the revelry outside Amerant Bank Arena in Sunrise, Fla., receded behind Edmonton’s bus — the best player in the world asked his family to be near him.

The family gathered in the living room of Connor’s suite. No one bothered to turn on the lights. They sat in the dark room, in silence.

There had been many disappointments throughout McDavid’s nine seasons in the NHL, as he rose to become the most dominant player of his generation. Usually, his mother, Kelly, could find the bright side in the frustration, but even she couldn’t comfort the son she spoke to nearly every day. Over the previous two months, Connor was so focused through four all-consuming playoff rounds that Kelly had heard from him only a few times.

After more than 10 minutes Connor’s father, Brian, finally spoke:

“The sun will rise tomorrow,” he said.

A simple statement of fact, whether or not they believed it. It was enough to jumpstart time.

“And I’ve got my son back,” Kelly said. “I’ve barely spoken to you in two months.”

“I know,” Connor said. “It’s been really hard, Mom.”

The Oilers had planned for dinner and a party at the hotel’s restaurant if the team won. They might as well make use of it, Connor suggested. And so, in the early hours of a new day, the family joined other Oilers players and families on the hotel patio, across from the ocean, like a gathering after a wake. They stayed there, together — mourning what was lost, finding small comfort in what was achieved — until it was almost light.

Connor McDavid skated away from the Panthers’ celebration after the Game 7 loss. (Elsa / Getty Images)

It’s a unique club to be a member of, being on the wrong side of a Game 7 loss.

Trevor Linden saw the sun rise as he drove home from Vancouver International Airport after an overnight flight from New York in 1994. Thousands of fans had gathered, waiting for the Canucks to land the morning after their loss to the New York Rangers in Game 7 of the Stanley Cup Final. There was a riot in downtown Vancouver, but Linden saw none of the damage. On the warm summer morning, Linden felt an eerie quiet as he drove toward his place in the beachside Kitsilano neighborhood. Hours later, he woke up and looked in the mirror. His nose was broken and he had two black eyes. He was skinnier than he remembered. His face was gaunt and pale.

“What a waste,” Linden thought. “You have nothing.”

Three decades later, he can still feel it.

“To think that 60 minutes could define your entire career,” he said. “You played 82 games and then two and a half months of the hardest hockey you’ll ever play. And it’s coming down to one game.”

That one game goes by in a blur — time speeding up as your team falls behind, until it’s over.

“The agony of defeat is never more real than when it comes down to Game 7 of the Stanley Cup Final,” Linden said. “That emptiness at the end — it’s hard to explain.”

J.S. Giguere waited awkwardly on the ice while the New Jersey Devils celebrated their Stanley Cup win after Game 7 of the 2003 final, having been told he’d won the Conn Smythe as playoff MVP — the last member of a losing team to win the award until McDavid won it in June. None of his teammates were aware of the win. He left the trophy in the hall when he joined them. Giguere had put up the performance of his career, but felt no joy in the accolade. Players sat silently, in tears, reflecting on what was and could have been.

“It was almost like a funeral,” Giguere said.

The Ducks goalie also looked in the mirror. His bushy playoff beard had irritated him for months. He shaved it off in the locker room that night in New Jersey before finally joining his family in the hallway and heading to a tarmac for the long journey home. He’d never grow a beard again.

It took Chris Pronger 13 years to get to Game 7. After the Oilers lost to the Carolina Hurricanes in the 2006 Stanley Cup Final, he sat with his teammates in the hotel lobby, sharing cold beers and finding small comforts in the journey — how they’d battled since January just to make the playoffs, and then forced a final game after trailing the Hurricanes through the final.

“You were so close to coming out the other side happy and excited and spending the next three months champion,” Pronger said. “And then you lose Game 7 — and what’s next? … There is no Game 8. This is the end. There is no next day.”

Goalie J.S. Giguere is consoled by teammate Keith Carney after the Ducks’ loss in 2003. The playoff beard disappeared soon after. (Al Bello / Getty Images/NHLI)

McDavid’s bachelor party, long planned, was scheduled to begin two days after Game 7. There was little interest in discussing the logistics as the Oilers moved through the playoffs last spring, so the inconvenient timing wasn’t addressed until the aftermath. The plan was to fly to Amsterdam, then on to Berlin to tour the city and catch a match in the ongoing UEFA Euro championships. Afterward, they’d hit up London for a Kings of Leon concert.

But the elaborate itinerary was scuttled. Leon Draisaitl and Darnell Nurse were part of McDavid’s wedding party, and everyone agreed this was no time for a European adventure. His brother, Cam, and Adam Phillips, Connor’s close friend and agent, were in charge of planning and quickly called an audible. The group secured a friend’s residence at Albany Bahamas, a luxury resort community in New Providence — which counts Tiger Woods and Justin Timberlake as shareholders — that welcomes many celebrities as guests, shielded by a no photo, no autograph policy.

The weekend after the loss, they relaxed in a hot tub on the patio, spent time at the beach, and tried to play golf. The group’s tee time was delayed by two hours because of rain. They finally managed eight holes before it poured again.

But being in the Bahamas during hurricane season provided some quiet amid the storms. The song “I Had Some Help” by Post Malone and Morgan Wallen played frequently all weekend. (McDavid is a big country music fan.) He tried to embrace the celebration — but the emotional loss was difficult to escape.

“It was a bit of a weird time,” McDavid said.

On the last night, McDavid sat in the residence’s theater room with Cam and Adam. They stayed up late, reflecting on life, while watching John Mayer videos on YouTube and listening to songs by Pat Robitaille, a Canadian musician who Connor invited to sing during his proposal.

“There was a lot of talking amongst everybody,” McDavid says. “In a way, it was nice to decompress, but at the same time it was a little bit strange. You’re supposed to be celebrating and having a good time, but at the same time it was … not that way.”

After a couple of days, while the winners still buzz, the losers pack up their gear, speak to the media, do their exit interviews and then get out of town.

Pronger went to Mexico with his wife to heal his busted back, throbbing knee, swelling elbow and lingering regrets.

Linden escaped to his cabin on a lake in Montana to work through the pain.

“It’s a loss,” Linden said. “It’s a mourning.”

Giguere went to Nova Scotia for his wedding, just six days after losing Game 7. The couple never expected the Ducks to play so long into June, so they set a date for June 21 and stuck with it.

The time away helped, but the unfulfilled anticipation still haunted each of them. And then life moves on. There are trips to take, weddings to celebrate, kids to tuck in. After the New Jersey Devils lost in Game 7 of the 2001 Cup Final to the Colorado Avalanche, Scott Niedermayer found comfort in his newborn son and toddler, returning to the mountains and nature of Cranbrook, British Columbia.

“That really helps with your perspective,” he said.

It also helped that Niedermayer had already won two Stanley Cups with the Devils, including the season before. Two years later, he would win another in Game 7 over Giguere’s Ducks: “Maybe I’m not the best example.”

But even for Niedermayer, the one that got away still stings.

“You’re just getting up and doing what you’ve got to do, without a real sharpness to your day,” he said. “That’s the state you’re in after two months of playoff hockey and 82 games.”

Eventually, they each turned toward a new season.

For Scott Niedermayer, right (with his brother Rob and mother Carol in 2007), a Stanley Cup is the only proper ending to a playoff run. (Jim McIsaac / Getty Images)

McDavid took longer than usual to return. A younger version of him would have jumped right back into training, obsessed with improving any weakness, however small. But nine seasons into his career — three Hart trophies as league MVP, five Art Ross trophies as the league’s point leader, zero Stanley Cups — McDavid has learned to understand that pushing too far forward can be a step back.

“Coming out of last summer and into the season I was tired, I overworked my body. I got injured right off the bat and was playing catch up all year,” McDavid said. “I didn’t want to do that.”

He spent a couple weeks in early July at his Muskoka cottage with his fiancee, Lauren Kyle, and his family, as they prepared for the wedding in early August. He’s found solitude on the lake’s dark waters after past disappointments — a first-round loss, a conference final loss, a second-round loss. Each carried its own frustration and unique physical and mental pains to overcome. But reaching the furthest point and falling short brought a new exhaustion. And the wedding was just weeks away.

“Life came at us like a firehose,” he said. “We were going through a range of emotions. You focus on the run and then all of a sudden it’s the end of playoffs and we’re right into things.”

At the cottage, McDavid did all the small things he loves. Sitting in the sauna before a cold plunge. Hitting balls in the golf simulator. Swimming. Boating. Wake surfing. Tennis — and pickleball, lots of pickleball. “I’d hate to call us big pickleball guys, because it doesn’t sound cool at all,” Cam said. “But we definitely play a decent amount of pickleball.”

McDavid started training by mid-July, working out with Draisaitl at St. Andrew’s College north of Toronto, under the guidance of his longtime strength coach Gary Roberts.

A couple weeks later, the first weekend of August, McDavid and Lauren were married on a custom-made floating dock in Lake Muskoka. Over a four-day event, they celebrated with their closest friends on Old Woman Island, a private archipelago on the lake lined by multimillion-dollar estates. Cam stressed over the best man’s speech, but landed the right punch lines and spoke about Connor’s quiet nature, huge heart and the pride he takes in looking up to his little brother. Later, Connor and his mom danced to “My Wish” by Rascal Flatts. The music carried through the night, echoing across the water.

After the wedding, Connor and Lauren continued to spend time with family, visiting his parents at their place on a lake in Collingwood several weekends in a row, along with his brother and his fiancee. The McDavid family has always been tightly knit, but there seemed to be even more effort to eschew busyness and be near each other through the few weeks they had.

“There was something different about this summer,” Kelly McDavid said. “It seemed like Connor wanted to be close to the family.”

Today, Giguere takes pride in being one of only six players to have won the Conn Smythe despite playing for the losing team. He’d pulled off the greatest performance of his life. But as a child, he didn’t dream about holding an MVP trophy.

“You’re there for the Cup,” Giguere said. “There’s not one day that has gone by that I would not take that trophy and trade it to get a second Cup.”

When the Anaheim Ducks met the Ottawa Senators in the 2007 Cup Final, the agony of the past loss seemed like a benefit to Giguere.

“You know the energy it took to get there. The sacrifice. The hope that you’ll get another chance,” he said. “I think this is where the experience comes in, once you get to it again. … Any mistake that you did the time before, you’re not going to do again.”

When time ran out on Game 5, Giguere leapt into the air and embraced Ryan Getzlaf and Corey Perry. Gary Bettman handed the Stanley Cup to Niedermayer, who had captained the team he’d beaten in 2003. Winning helps mute the pain of a past loss, but it never fully goes away, said Pronger, who’d joined the Ducks a season after losing Game 7 with the Oilers. But if it was your only chance, it lives with you in a unique way. He recalled seeing the faces of the oldest players on the Oilers when they lost in 2006, knowing they’d likely just missed their last opportunity to win the Cup. Their tears resonated.

“You never know how many years you’ve got left,” Pronger said. “You never know when your time is going to come.”

Connor McDavid is back and ready to take another run for that elusive Stanley Cup in 2024-25. (Steph Chambers / Getty Images)

Outside the Oilers locker room, a young boy stood next to a rack of sticks, smiling for a photo next to the few marked No. 97. At the end of the short hall, before the locker room doors, a display held five replica Stanley Cups — marking an earlier era of Oilers greatness.

The trophies, shining in overhead light, sat slightly off-center with an open space at one end.

Just beyond the wall, McDavid sat in his stall, trying to describe what carries forward after losing a Game 7, how it lingers and how it shapes you. Told about conversations with several players who’d been through the same, he said, “I’m interested to see what some of the other guys say on how they deal with it.”

He’d just finished his first preseason game, scoring a goal and assist in a 6-3 loss to Calgary. Afterward, a scrum of reporters asked him about a viral clip from an upcoming documentary that showed him berating his team after losing the second game of the final to the Florida Panthers.

“That’s not good enough!” McDavid shouted. “Dig in. Right now.”

The outburst surprised even those closest to him, like Cam. It was a rare eruption of the inherent intensity that drives him. The Oilers would drop another game and were on the brink of being swept, but they stormed back to force that fateful Game 7.

The Oilers captain said he still hasn’t thought much about the Conn Smythe he won. He meant no disrespect by skipping the on-ice presentation while the Panthers celebrated, he said.

“I thought it was important to spend those moments with the guys.”

The replica trophy McDavid was given hasn’t played a prominent role in his expansive collection of individual accolades.

“Ah,” he said. “It goes with all the other ones.”

Entering his 10th NHL season, McDavid still doesn’t seem interested in his status as the best player of his generation. He is 18 points short of 1,000 — and will become the third-fastest player in league history to reach the milestone behind Wayne Gretzky and Mario Lemieux, if he does it in fewer than 11 games.

If he does, the accomplishment will go “with all the other ones.”

McDavid is eager to move forward.

“You learn a lot about yourself going through that run. You learn a lot about your teammates going through all that stuff. And I think everyone just has a sense of calm about it, which is comforting,” McDavid said. “You’re never going to play in a bigger hockey game than that one.”

The room was empty now. It was late, with another day just hours away.

“It’s hard to put into words but you know time moves on. Life moves on,” McDavid said. “And you’ve got to get ready to go again.”

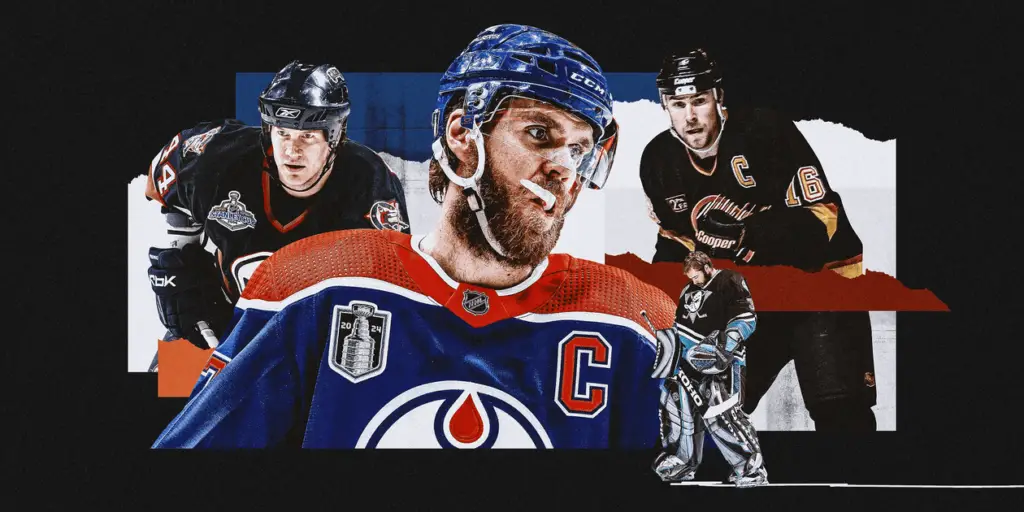

(Illustration: Meech Robinson / The Athletic. Photos: Codie McLachlan / Getty Images; David E. Klutho / Sports Illustrated via Getty Images;

Graig Abel / Getty Images; Dave Sandford / Getty Images/NHLI)