DETROIT – Zach Edey unfolded a brown blanket across his legs in the first aisle seat on the right, and Lance Jones carefully tucked the Midwest Regional trophy into the seat beside him. The flight attendant congratulated Purdue on its 72-66 victory over Tennessee in the Elite Eight. The plane taxied, took off and, 52 minutes later, landed in the middle of catharsis.

Purdue on Saturday will play NC State in its first Final Four since 1980, and a program so long tethered to its failings finally has a reason to celebrate. And so they came, students leaving Harry’s Chocolate Shop, where the chocolate is merely a descriptor and the bar is the heart of the matter, and grown-ups packing up their kids as if going to a parade. They jammed the tiny airport parking lot in West Lafayette, Ind., to capacity, forcing late arrivals to ditch their cars on the grass and police to come to create some order.

By the time the Boilermakers touched down, fans stood 10 deep on either side of the road, from the metal gates that led to the tarmac at one end, all the way to the traffic light at the other. Three hundred? Four hundred? The dark made counting tricky, but there were enough people that everyone who disembarked from the plane stopped and stared. “This is crazy,’’ walk-on guard Chase Martin said.

After collecting their bags, the players awaited their ride on the tarmac side of the gates as if waiting in the wings to take the stage. Finally, they boarded the Boilermaker Special, Purdue University’s “official” mascot, which could be best described as a Victorian-era locomotive replica plopped upon a pickup truck, its open-air bed big enough to hold half a basketball team. After the first crew left, the Special returned to collect the rest, including Edey, who climbed aboard with the net looped around his neck, and Mason Gillis, who hoisted the trophy above his head. With three honks from the train, the Boilermakers rolled through a crowd near delirious with delight, and on to the national semifinal.

“That was so cool,” one little girl yelled to her dad. “You’re only 7,” he replied. “Do you know how long I’ve been waiting for that?”

Matt Painter is sitting on a dais at the NCAA Tournament Midwest Regional. The next day his top-seeded Boilermakers will play Gonzaga in a Sweet 16 game, their fifth regional semifinal in the last seven years in which there has been a tournament. He has enjoyed the immense good fortune to turn the game he loves into a job that never feels like work. But he is not asked about his excitement. Instead, he’s confronted, yet again, with his failings, a laundry list of painful upsets that most Purdue fans can recite by memory: 12th-seeded Arkansas-Little Rock in double overtime in the 2016 first round; 13th-seeded North Texas in overtime in the 2021 first round; 15th-seeded Saint Peter’s in the 2022 Sweet 16; 16th-seeded Fairleigh Dickinson in the 2023 first round.

“The game,’’ Painter says, “doesn’t always love you back.”

It has, frankly, spit in Painter’s eye, a love so unrequited it borders on cruel. Yet here he sits, on the first day of March, the month of his reckoning, at the head of a table in the conference room that serves as his headquarters. He logs many an hour here, surrounded by the detritus of the basketball mind first piqued in childhood and still burning 40-some-odd years later. File folders lay strewn on the floor behind him, basketball books pile up on a nearby table, whiteboards blanket either wall, each covered with Einsteinian basketball scrawlings, and in front of him sits a haphazard collection of papers, Post-it notes and a bucket of pens, ready to record Painter’s latest hoops musing.

When asked if he’s purchased a stuffed monkey for his NCAA Tournament trip, Painter raises his eyebrows quizzically. “A what?” he says. He is told of the tale of Tony Bennett, how the Virginia coach ran into his team’s locker room after its 2019 first-round exorcism win over Gardner-Webb with a monkey riding piggyback on his shoulders. Upon entering the locker room, Bennett threw the toy onto the ground to complete the metaphor. (In an ironic twist a week later, Bennett and the Cavaliers would advance to the Final Four and ultimately win the title at the expense of Painter and Purdue, ousting the Boilers in an overtime classic in the Elite Eight.)

Painter laughs to himself. “I should probably get a piano,’’ he says.

The burden of Purdue, metaphorically as heavy as a baby grand, can best be summed up by a barista making small talk with a co-worker at the Union Club Hotel coffee shop on campus. She’s chatting about her upcoming travel plans and sighs. “How likely are we to go to the Final Four this time?” she says. “I want to save money for a flight, but are we actually, like, going to go this time?”

This is the crux of what it is to be a Purdue basketball player, or a Purdue basketball coach. It is to build a program that is so good, so steady, so reliable that it creates hope, breeds optimism and allows for the best and nastiest thing in all of sports – expectation. Yet it is also to build a program that fails just enough that the hope comes tinged with fatalism, the optimism tempered by a slight twinge of disillusionment, and the expectations feel more like anvils than assets.

In 1980, long before the barista entered the world, a feisty sixth-seeded Purdue team made the Final Four in the first year in which the tourney bracket was expanded to (a quaint) 48 teams. In the 44 years since, the Boilermakers have won 958 games, 11 Big Ten regular-season titles and two league tournament crowns. They’ve made it back to the bracket 32 times, and suffered only five losing seasons. They’ve reached eight Sweet 16s, and three Elite Eights. But had never reached another Final Four.

Some of it belongs to Painter. His flameouts have only added to the soundtrack of Purdue’s misery and he is well aware of it. When a reporter begins a question by suggesting that “in all probability” the Boilermakers will beat Utah State, Painter answers politely, if directly, in the news conference. Later, as he returns to the locker room, he laughs. “How about that? I wanted to say, ‘Have you heard of Fairleigh Dickinson? No? How about Saint Peter’s? Oh wait, I have another one. How’s North Texas?’ I could go on, man.”

But Painter has been in charge for only 19 of the 44 years. The other 25 belong to the only big-name coach who recruited him out of Delta High School, Gene Keady. Keady recently moved back to West Lafayette from Myrtle Beach, S.C., and is very much along for this tournament ride. And because he was Keady’s player and his assistant, Painter believes that, if his failures can be claimed as some systemic problem, surely his success could be an affirmation. “Of course it bothers him,” says director of basketball operations Elliot Bloom. “It’s such a bigger burden than if he were somewhere else. He wants to do it for so many people around here – people in the athletic department, fans, people on campus, former players, Coach Keady. Especially Coach Keady. That’s a big group to come through for.”

Yet Painter has spent the past month like a man without a care. On the bus to and from practice or games, he either spins yarns about whatever random topic bounces through his busy brain, or he plays his daily dose of the Immaculate Grid, MLB version (he’s a huge Cubs fan). He drops one-liners in scouting reports — as he’s talking about Utah State big man Great Osobor, he stops as he discusses the isos the Aggies run for Osobor. “Isos for Osobor,’’ he says. “The man should open a restaurant.’’ He inserts pearls of wisdom in his news conferences – “In society, when you run your mouth, your percentage of getting your ass kicked goes up.’’ On a long soliloquy about how to feed the post, Painter name-dropped Wayman Tisdale. The four players to his left – Braden Smith, Jones, Fletcher Loyer and Edey – all looked at each other confused. “Sometimes he says someone I at least heard of,” Edey says. “No idea who that is.’’

This is who Painter is, an easygoing person in a profession meant for maniacs, with a brain that houses so much knowledge he can’t help but regurgitate it. It is, however, purposeful. As heavy the yoke of his burden weighs, it falls in equal measure on his players. He has spent the entire season telling them to own up to their mistakes, particularly the FDU disaster, but not sacrifice the joy of this season for the misery of that one. They have largely followed his lead. The Boilers get their work done in practice, but it never feels like they’re walking on a tightrope. Jones and Smith spent an entire shooting drill discussing the merits of chocolate milk. Trey Kaufman-Renn, a lover of philosophy, asked Loyer what sorts of questions annoy Loyer when Kaufman-Renn gets overly philosophical. “That one,’’ Loyer deadpanned. Assistant coach Brandon Brantley, as he pounded Edey with pads, loudly sang “O Canada” to the Toronto-born big man.

At night, some of the players gather in the hotel conference room to play poker – not particularly well, mind you, but with dedication. Loyer wandered around Detroit killing time before the Sweet 16 game against Gonzaga, and Edey, a self-described excellent napper, dozed off twice in the afternoon before the game.

On the morning before the biggest game of their season, the Boilers gathered in Woodward Ballroom C of the Westin Book Cadillac in downtown Detroit. Assistant coaches Terry Johnson and P.J. Thompson broke down film about the Vols, Painter chiming in from the back of the room. They cautioned the Boilers not to fall prey to what would no doubt be a physical, and potentially foul-infested, game. “It’s going to be hand-to-hand combat,” Johnson said. “Don’t get into it. Don’t look at the officials. Play your game.”

They wound up the 30-minute session with Painter sending the Boilers off with a simple directive: “This has nothing to do with them. This is about us.”

On the bus to practice, Loyer passed out homemade cookies.

Edey is meant to be in the Purdue locker room for interviews. Instead he is plopped on a sofa inside a suite just off the media room at Gainbridge Fieldhouse in Indianapolis during the tournament’s opening weekend. The space feels less like a sports arena and more like a private room in a club, all muted colors and weird lighting, and Edey laughs at the vibe as he walks through. He would prefer to be talking to no one – he’s already kiddingly chided Chris Forman, the team’s strategic communications director, about being done with media – but given the choice of a one-on-one versus a scrum, he’s opted for the least painful variety of conversation.

The pivot winds up perfectly timed. After a slow shuffle back to the locker room, Edey walks in as the NCAA attendant shouts that media access will be ending in one minute. Ten TV cameras swarm Edey as he sits. Sixty seconds later they are shooed out. He repeats the process a week later in Detroit, choosing to lean against a wall and chat rather than go back to the locker room. He is not being a diva. When he answers questions, he’s unfailingly polite, insightful and pleasant. He’s just over it.

Over the attention, over talking, kind of over himself.

“Everybody wants to be that guy,” says senior guard Ethan Morton, one of Edey’s roommates. “But there’s also a lot of sh– that comes with it, and nobody gets that. I don’t think people understand what he has to deal with, and the weight he carries on his shoulders. He’s got a master’s degree in dealing with sh–.’’

The albatross of expectation has stretched across the shoulders of all the Boilermakers this season, but it rests most heavily on the very broad ones of Edey. Now or never is a ridiculous proposition in sports, but if Edey is a 7-4, 304-pound once-in-a-generation player, well, then, it would follow that the Boilermakers have the cheat code to win it all.

It is hard to understand what it is to be an overgrown person in a world of average, to constantly feel the eyeballs of the curious in a world that is not built for you. To walk off a bus, Edey bends in half at the waist, holds on to the front seat, contorts down the two steps and ducks under the doorframe. His post-practice ice baths are at the arena because he simply won’t fit in the hotel bathtubs. “Why is he so big?” a Grambling State fan whined during the first-round game against Purdue. “How can he be so big?”

Gawkers have been part of his life for as long as he can remember. “I’m a tall Asian guy,” he says. “I was an anomaly even before I started playing basketball.’’ As Edey headed to the bus for a Saturday practice prior to the regional final, a fan waiting on the sidewalk along Michigan Avenue screamed, “Look at him! There he is!”

Now mix in the fame that has found him, the autograph seekers and fans poised with cameras, and maybe it’s easier to understand why he opts to DoorDash rather than go out, or avoid interviews about himself if he can.

He is more than a curiosity; he is about to become the first back-to-back national player of the year in 40 years – since Virginia’s Ralph Sampson. He is inarguably the most recognizable face in men’s college basketball. During an off day in Indianapolis, Edey shuffled past an empty suite on his way to yet another interview – this one with CBS. The place was empty but the TVs were still on, showing the studio hosts, with Edey’s picture in the background, clearly discussing him. It felt like a funhouse – dozens of Zach Edeys as Zach Edey silently walked by.

He is also the most divisive player in the game. No one leaves an Edey-officiated game content – Purdue fans convinced he’s being hacked, visitors certain he’s doing the hacking. It’s led to an almost weaponization of his height. “You’re only good because you’re tall,’’ a Utah State fan screamed during the second-round game. “And you get all of the calls.’’

Edey did not arrive at Purdue prepared for any of this. Ask him what he was ranked coming out of Toronto and he doesn’t hesitate. “436th,’’ he says, adding, “My freshman year, I wasn’t really good at anything.’’ He’s not entirely right – he averaged 8.7 points per game and, bumped it up to 14.4 and 7.7 as a sophomore – but nothing foretold what was coming. Even as recently as a year ago, Edey wasn’t exactly on the radar. North Carolina’s Armando Bacot and Gonzaga’s Drew Timme garnered most of the preseason player of the year picks. The Big Ten opted for Trayce Jackson-Davis, not Edey.

“People act like he was Patrick Ewing walking through the door,’’ says Brantley, who works with Edey and all of the Purdue big men. “He’s a good dude. No bullsh– and he’s worked so hard. I don’t understand. Why is the kid hated on? He should be a kid you’re rooting for.’’

Former assistant coach Steve Lutz, who recruited Edey, gave him a shooting routine that Edey commits to religiously. So intrinsic is it to Edey, it is now built into the Boilermakers’ road practice plans. No one can leave until Edey is done, so Painter figured he might as well give everyone else something to do. Consequently, at the end of a pregame practice at NAIA Marian College in Indianapolis, Painter yelled, “OK, free throw contest. Zachary, you go down there with Tommy.’’ The rest of the players essentially played free-throw knockout and then dissolved into elementary schoolers at recess, catcalling the players who missed or trash talking the ones still shooting, Edey went off to a basket alone with grad assistant Tommy Luce.

He stood under the right side of the basket and shot 10 hook shots with his right hand, followed by 10 with his left. He did the same, 10 and 10, but this time using the glass. Then came 10 hooks from the baseline right-handed and 10 more left-handed. Edey repeated the sets in front of the basket and on the left side of the hoop, his own version of around the world. Every time he missed, he subtracted one until he got to 10, eventually putting up 180 shots. As a freshman, it took him upwards of 25 minutes to finish. On this particular day, he only missed eight shots and finished in under eight minutes.

Edey worked, got better, got really good and then was told to deliver Purdue to a place it hasn’t gone in 44 years. “People, a lot of them don’t give me credit for anything,” Edey says. “But I don’t do the work for other people. I don’t care if they see it or appreciate it. I do it for myself. I do it for my family. And I do it for my teammates. And now we’re on the cusp of history.”

Purdue’s Zach Edey scored a career-high 40 points in the Elite Eight against Tennessee on Sunday in Detroit. (Mike Mulholland / Getty Images)

Of course history did not come easily. How could it possibly? Not for Purdue, not for a program that has specialized in angst for 44 years. “Empty your tank,’’ assistant coach Paul Lusk instructed the Boilermakers before they took the floor Sunday against Tennessee. They came back well depleted. “I’ve never been in a game this hard and this physical in my life,’’ Smith said.

And when history was finally secured, the Boilermakers went through the rituals of winning. Edey sprinted over to Painter, interrupting the coach on his way to shake hands with Volunteers coach Rick Barnes, and wrapped him in a bear hug. The Boilers all donned their T-shirts and hats declaring them Midwest Regional champions. Loyer slapped the bracket with the Purdue placard on the Final Four line – upside down at first – and they snapped pictures and scooped up the confetti.

Edey called his teammates over to assemble behind him for his interview with CBS. They then doubled over in laughter after he dropped an F-bomb – “four f—ing years,’’ he said. “That wasn’t me,’’ Edey said. “It was like an out of body experience. I don’t even know what I said.’’ Edey then wandered off to collect confetti. One month earlier, after they’d wrapped up the Big Ten, he popped the case off of his phone and tucked a few glittering snippets there, vowing to collect so much that the case wouldn’t close.

Loyer wandered around, looking for people to high-five and climbing over a bunch of TV wires to celebrate with the pep band. “I think I actually might cry,’’ he said. Jones, who has never entered a room he couldn’t own, was, for perhaps the first time, out of words. “I’m not sure I know if I can even feel it yet,’’ he said.

Later, they ransacked the locker room, peeling off the decorative placards for souvenirs and carrying them onto the bus and eventually onto the plane. They checked their phones. Painter had 428 text messages waiting for him.

And, of course, they climbed the ladder (or in Edey’s case, reached up) and snipped the nets. Julia Edey, recording her son from a seat behind the bench, shook her head as an entire arena erupted. “What the frick is happening?” she said. “This is unbelievable.’’ As he did after the Boilermakers won a share of the Big Ten regular-season crown, Edey took a piece of the net to Keady, removed the older man’s hat and tied it to the back.

Amidst the mayhem, Painter stood quietly near the 3-point arc and watched. He’d had his moments. A Westwood One radio interview with Robbie Hummel, his former player, turned so emotional that both struggled to speak, and watching Edey with Keady, Painter ran out of words. “He’s 75, late in his life, and to see that …’’ he said, before stopping.

Painter’s wife, Sherry, eventually made her way to her husband, the two meeting at the top of the 3-point line as the players and staff took turns with the scissors.“Are you going to cut the nets down this time?” Sherry said. A month earlier the coach opted out of the ritual after the Boilermakers won the Big Ten share at Mackey Arena. “It’s just not my thing,” he said. “I don’t like the attention.” But Sherry persisted, and Painter reluctantly turned, grabbed a pair of scissors and climbed the ladder for arguably one of the fastest net snips in NCAA Tournament history.

Upon descending, he turned to his wife and smiled, “At least I didn’t fall.”

No, finally, Painter didn’t trip and Purdue didn’t fall. The last notes of the piano have faded away.

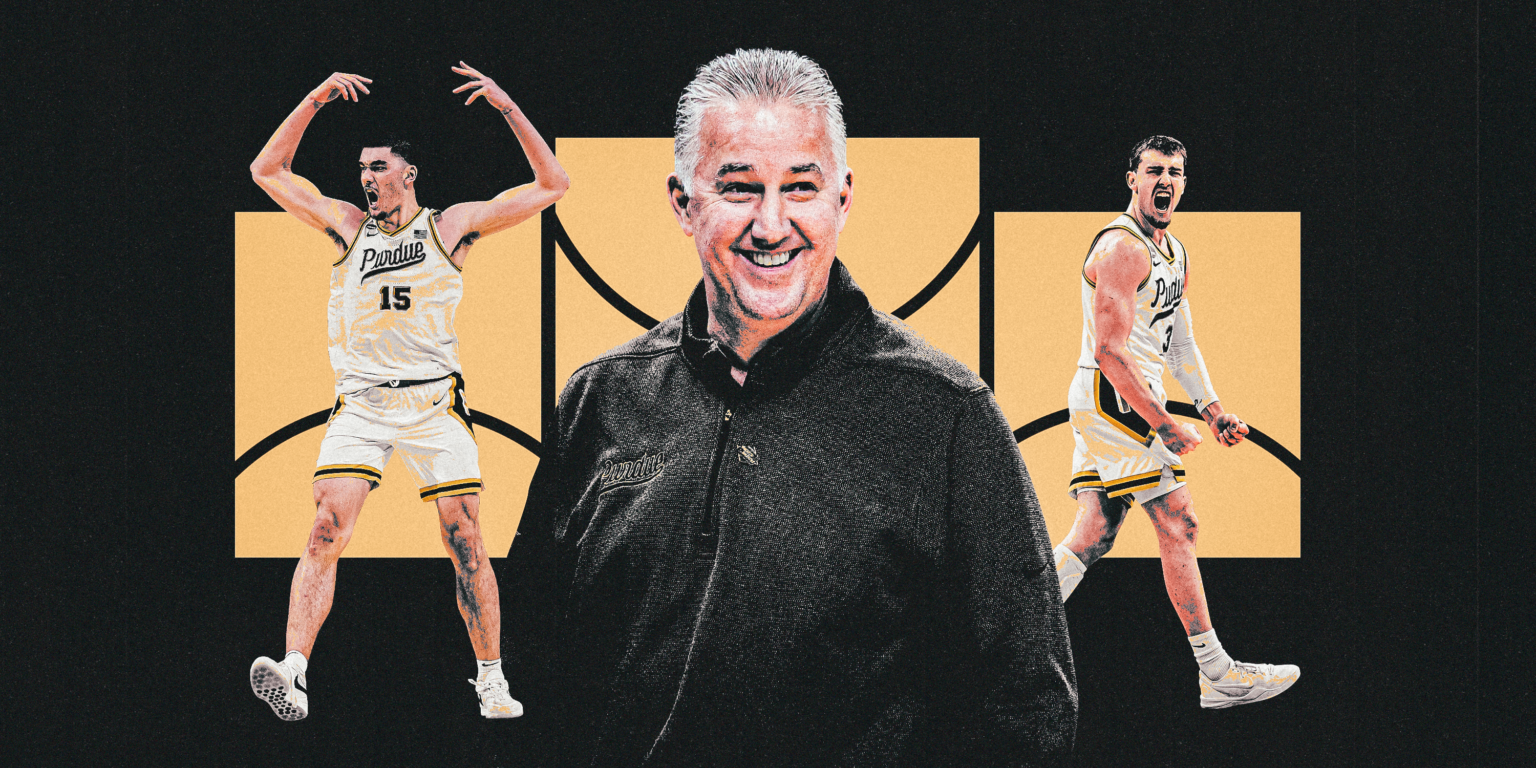

(Illustration: Dan Goldfarb / The Athletic; photos: Mike Mulholland, Andy Lyons / Getty Images; Ben Solomon / NCAA Photos)